by Lucia Messent

Content warning: this article mentions sexual violence

In October 2017, actress Alyssa Milano urged Twitter followers to reply ‘me too’ if they’d ever been sexually harassed or assaulted. More than 60,000 responded, and within a year #MeToo had appeared in an estimated 19 million tweets spanning 85 countries.

For the fifth anniversary of Milano’s Tweet, I contributed to an ActionAid UK article reflecting on the importance of #MeToo. I found that the Americanised, celebrity-focused version did little to account for intersectional experiences of sexual violence, making it far too selective in the voices it amplified. This article is a follow up focused on trans-Atlantic perspectives of #MeToo. I offer a more thorough exploration of the gaps in the movement, in the belief that only after reflection can we ensure next time, we leave space for all voices to enter the discussion.

“There’s no conversation in this whole thing about transgender folks and sexual violence. There’s no conversation in this about people with disabilities and sexual violence. We need to talk about Native Americans, who have the highest rate of sexual violence in this country.” – Tarana Burke

The quickest way to pinpoint where #MeToo fell short is by examining which demographics are most vulnerable to sexual violence. According to the Office for National Statistics, the groups most at risk in the UK are people under the age of 14, adults of Black or Black British and Mixed ethnicity, women with disabilities, unemployed people, and students. Missing from this study is the data on queer folks and refugees, another two groups that are disproportionately impacted by the crime.

The more privilege a person has, the more protected they are from sexual violence. Yet, it was only when we heard from women like Jenifer Lawrence, Reese Witherspoon, and Gwyneth Paltrow that the world realised the crime’s pervasiveness.

It should come as no surprise that the celebrities who drove the MeToo hashtag did not coin the term itself. The founder was Tarana Burke, a community activist and woman of colour who used the phrase to build solidarity among young Black women who were survivors of sexual assault. Tarana has been a prominent figure in discussions around #MeToo, but only, as she explained in an interview with Verso Books, because she “inserted” herself in the conversation and refused to be side-lined.

In the same interview, Tarana expressed frustration that the online movement focused so much on individuals instead of examining broader social, economic, and institutional factors. “There’s no conversation in this whole thing about transgender folks and sexual violence,” she said. “There’s no conversation in this about people with disabilities and sexual violence. We need to talk about Native Americans, who have the highest rate of sexual violence in this country.”

Tarana also criticised the movement for its implied assumption that all survivors want the perpetrator identified and taken to court. She said: “what does justice look like for a survivor? It’ll mean different things to different communities. What I’ve found in my research is this: the process was you had to go to the local police station, report the crime, and then they would make a referral to the rape-crisis centre. I was appalled when I learned that. That’s a big hurdle for us, because we don’t trust the police.”

“I was assaulted during one of the initial peaks of Black Lives Matter. I’d been inundated with images of the police killing and harassing black people – I was like, I’m not about to ask them for anything – I don’t want to talk to ya’ll.” – Ja’Loni Owens.

Ja’Loni Owens is a Black, non-binary activist and law graduate living in New York. After experiencing sexual violence as a student, Ja’Loni made the decision not to report the incident. As well as believing that no policeman in their (predominately white) area would take the matter seriously, they also avoided the legal system because they were hesitant to put the perpetrator, a Black man, through the prison system.

“America has the most incarcerated people per capita,” they said. “And our legal system is more likely to punish marginalised folks… The prosecution usually doesn’t have to do much to prove guilt when the defendant is Black or Latino or gang affiliated, which means tons of these convictions reflect racial and class bias instead of justice.” Pointing out that prison is a place of increased sexual violence rather than accountability, the activist concluded: “if I’m trying to get this person who harmed me to confront how they harmed me…they’re not going to do that if they experience what I experienced… It would be much more transformative if we were to have some type of recourse that isn’t entangled in that system.”

“Since so many people of colour, especially undocumented folks, aren’t going to the police anyway, it makes sense to focus on ensuring survivors have the resources they need,” Ja’Loni continued. This includes secure housing, therapy, local support groups, and protection from dismissal if they require extended leave.

Noting the discrepancy between this community-based approach and the top-down, globalised approach of #MeToo, I asked Ja’Loni to share their thoughts on the movement. “There’s Tanana Burke’s Me Too,” they replied, “which has a focus on marginalised folks. Then there’s the Me Too we had a dialogue about online – that was focused on wealthy, white women, most of whom had direct access to legal avenues.” What the movement overlooked, Ja’Loni explained, is that celebrity experience cannot account for the experience of marginalised individuals: “if you’re an immigrant, for instance, there’s an extra level of vulnerability … you might be thinking: ‘my immigration status is tied to this employer who’s exploiting me in these ways’.”

Ja’Loni also felt that the hashtag revealed biases in the way we talk about victimhood. They pointed to Salma Hayek and Lupita Nyong’o, two women of colour whose allegations against Harvey Weinstein were immediately discredited by the public. “People would laugh online and be like, oh no, this is going too far now, I don’t think he would touch them,” the activist explained. “They’re beautiful, but as far as conventional attractiveness goes, they don’t fit that mould. And so it was easy for white men to say: ‘oh I’m not attracted to brown skinned women, so I don’t think he (Weinstein) would sexually assault them’.”

As well as discrediting the experiences of certain survivors, the narrative that sexual violence is about attraction only also conceals the power element of the crime. Sexual violence often occurs without any attraction at all, Ja’Loni explained, citing cases where white gay men touch Black women’s bodies without consent, or where straight men sexually assault queer people. “There are some people’s bodies they (the perpetrators) just feel entitled to touch and extract,” Ja’Loni concluded. “They don’t think of them (the potential victims) as full human beings who can consent or not consent to things.”

If sexual violence is about entitlement and power, then it is no surprise that those with the least privilege are the most likely to experience it. This is why context must be the centre of the conversation – not just a footnote.

Editor’s note: several of the quotes below refer to people with disabilities as disabled and people without as non-disabled. This does not reflect the ‘person-first’ ethos of Barriers to Bridges but has been left in for the purpose of direct quote accuracy.

#MeToo also overlooked the added barriers that survivors with disabilities may face after choosing to come forward. As Mexican-American journalist Emily Flores explained in an article for Teen Vogue, it is often presumed that people with disabilities are in some way removed from sexuality, making it harder for them to participate in discussions around the topic.

“I was conditioned to think that because of my disability, I was immediately excluded from being sexual,” Emily wrote. “And as I now navigate my adolescence, I see the glaring absence of the disability community in sex-positive conversations.”

Though the phrase ‘me too’ aims to connect all survivors, for some, the barriers remain in place long after they share their story. “The simple expression of saying ‘me too’ means to become liberated from sexual harassment and sexual harassment taboo,” Emily explained. “For the disability community, saying ‘me too’ means becoming rid of stigmas, rid of sexual assault, and rid of ableist ideals.” At no point during #MeToo were these additional obstacles brought into the centre of the conversation.

It was also rarely acknowledged that people with disabilities may experience sexual violence in different contexts, and often more frequently, than those who are not disabled.

Some disabilities may impede a person’s ability to give consent. People with disabilities may also be reliant on their perpetrator for care or support, making it harder for them to remove themselves from dangerous situations. This power dynamic is reflected in the fact that those with disabilities are almost twice as likely to experience sexual violence.

Street harassment is another particularly pressing issue for people with disabilities, as visually-impaired activist Dr. Amy Cavanaugh explained during a lecture at the University of Oxford.

“As I learned to use my new white cane… I started experiencing what I call ‘grabbing’,” said Amy. “And this varied from being dragged across roads, pushed into seats, even shoved onto trains I didn’t want to get on. In these incidents of grabbing and unwanted touch, there is frequently an absolute disregard of consent. Even saying ‘No, this will hurt me’ is ignored in favour of the perceived act of ‘good help’ by the non-disabled person.”

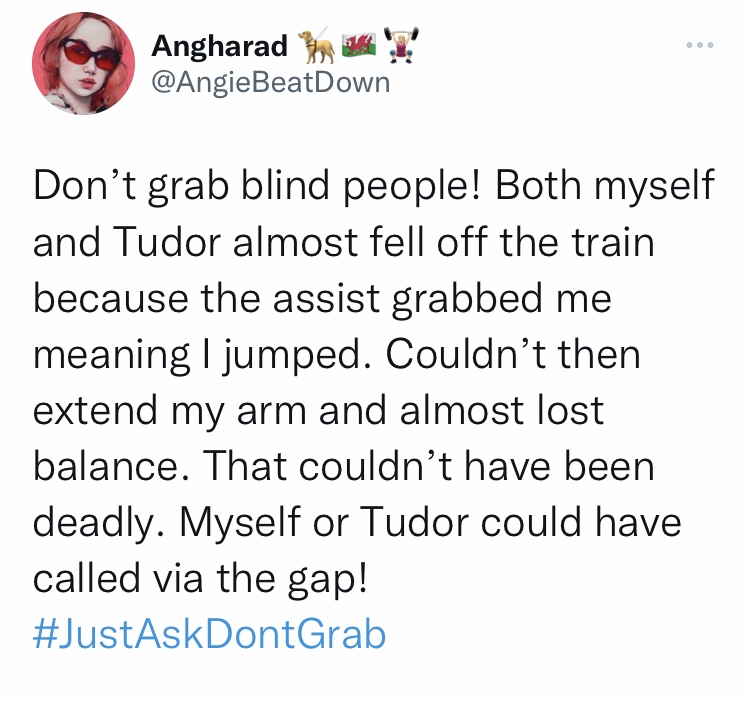

In 2018, Amy began her own Twitter campaign aiming to bring awareness about the nuances of harassment for people with disabilities. #JustAskDontGrab is still used on Twitter today, enabling users with disabilities to connect and share their experiences. I spoke with two people who had used the hashtag in recent years.

RainbowYeticorn, an American accessibility rights advocate, said: “a lot of the instances that happened to me were people grabbing me to ‘pray for me’ or children grabbing the joystick for my power wheelchair with no intervention from parents or adults. The worst is when medical professional start messing with the controls of my chair, trying to move me instead of treating me like an independent, autonomous, thinking person who can damn well move myself.”

Angharad, who is a Data Analyst and accessibility expert from Britain, said that people unwantedly grabbing her arm or touching her guide dog is a big issue. “I’ve even been harmed because someone brought their dogs to say hello to him (her dog), while I was crossing a road,” Angharad recounted. “This caused me to miss a curb due to the distraction.” Not only do people force themselves in her personal space without permission, they sometimes get offended when she asks them to leave: “one person told me ‘I’ll just let you get hit by a car and die then if you don’t want help’.”

What #JustAskDontGrab teaches us is that those with disabilities often experience an entirely different type of street harassment to that which #MeToo explored. For some, it is all-too-common to have strangers grabbing their bodies, ignoring their protests, and even becoming angry when they re-assert their boundaries. Beneath it all is the implied assumption that the right to refuse consent, a basic human right, simply does not apply to people with disabilities.

The hashtag also proves that social media campaigns can capture the nuances of sexual violence for marginalised communities. All it takes is reflection, an awareness of privilege, and a refusal to take context out of the conversation.

In no way was #MeToo inherently bad. Even today, the movement continues to unite survivors and motivate change. But, like all revolutionary movements, its impact will remain limited for as long as it is dominated by voices at the top.

© 2022

interesting thankyou